A party game in which deception, manipulation and accusation are compulsory? Sign us up. Werewolf isn’t for the faint-hearted, but as we discovered at the 2019 PokerStars Caribbean Adventure (PCA), it’s become the preferred after-hours pastime for many of the best poker players in the world.

It’s gone midnight in the Bahamas, and Day 1 of the PCA $25K High Roller has just come to an end. Dozens of poker superstars flock out of the Atlantis tournament room, each with their own plans for the early morning hours. For some it’s straight to bed, for others it’s dinner time.

But as we stroll through the lobby of the Coral Towers en route to our hotel rooms, we notice a large group of recognisable faces who have chosen to spend their evenings doing…something. They’re sat around in a circle. Their eyes are firmly closed. They’re slapping their knees with both hands simultaneously as one person walks among them, seemingly calling out orders. Was this meditation? Was it a cult?

Just what the hell had we stumbled across here?

Fast forward 24 hours and we’re making the same post-work trip through the lobby. What do you know? The poker players are back, and this time there’s even more of them. Sam Grafton, Scott Seiver, Dietrich Fast, Jonathan Jaffe, Max Silver, Calvin Anderson, Ole Schemion, Jerry Wong, Toby Lewis, these are just a few of the poker players we see over the next couple of nights, getting together for…whatever this is.

At some point during the PCA, curiosity gets the better of us and we enquire. It turns out this behaviour was nothing to do with meditation, nor was it a new cult. They were simply playing a parlour game called Werewolf. And as we soon discovered, it’s a game so perfectly suited to poker players that it’s no surprise many of the game’s best returned night after night.

MAFIA CONNECTIONS

Werewolf’s premise is simple: players are split into “villagers” and “werewolves”, with the former trying to kill off their enemies before they become outnumbered by them. Through debates and false confessions, outright lies and devious manipulations, the werewolves must do whatever it takes to survive. If they can kill off enough villagers, and get the villagers to turn on one another instead, the beasts win. (Full rules are below.)

If the outline sounds vaguely familiar, there’s a chance you could have played it under its former guise. That was the case for Sam Grafton, one of the players registering for the Werewolf games each night at the PCA.

“I first played it at my university under the name of ‘Mafia’,” Grafton tells me when we finally get the chance to untangle the mystery of Werewolf. “Then a couple of years ago a big group of us rented an Airbnb in Australia and we just played it until 4am, every night.”

Mafia was invented in 1986 by a Russian high-school teacher named Dmitry Davidoff, with the roles of villagers and werewolves taken by “innocents” and “the mafia”. Davidoff taught the game to his students as a way to distinguish right from wrong, and its immediate popularity prompted him to introduce the game to the Psychology Department at Moscow State University a year later. He pitched it as a perfect blend of psychological examination and team-building strategy.

Word of the game soon spread. It became commonplace in Soviet colleges and schools throughout the 1990s, and at one point became so popular that it formed the basis of a Latvian reality show, with celebrities pitted against one another. However, an influential interactive fiction writer named Andrew Plotkin felt that Mafia could be improved, and that its name was holding it back. His argument was that the mafia was not a big enough cultural reference in 1997, and he landed upon an even more appropriate theme. The game — played out over “night” and “day” phases — is all about hidden enemies who, while seemingly innocent at day, become evil at night. Hence, the werewolf.

Andrew Plotkin (photo courtesy of Ben Collins-Sussman)

“I was fascinated with the game design,” Plotkin told wired.co.uk. “I had never seen a game with such a pure strategic underpinning — no mechanics to be strategic about. It was what poker would be if you didn’t play with a deck of cards, but bet solely on other people’s bets. It shouldn’t have worked, but it did.”

Grafton agrees. “The game really is so much fun,” he says. “The reason it’s great for dinner parties is that when you’re a wolf and you’re trying to win with the other wolves, it’s really bonding. When you believe someone and it turns out they’ve deceived you, it’s really discombobulating. But it’s definitely a lot of fun.”

HOW TO PLAY WEREWOLF

One of the best things about Werewolf is that you can play it anywhere there’s a big group of people, whether it’s with friends and family around the dinner table, or after long days on the poker grind.

At the very beginning, one player is assigned to be moderator, and it is this person’s job to keep the game running smoothly. (Typically the role will switch at the end of each game.) A minimum of seven other players are then split into two groups: werewolves and villagers, with the former in the minority. The moderator deals a card to each of the other players to determine their role. The ultimate aim of the game is for the villagers to kill all of the werewolves, or for the werewolves to outnumber the villagers.

Players don’t reveal their roles until the end of the game — this is Werewolf’s central mystery. The villagers should always be at a majority of around 3:1, so if there are eight of you, you should have two wolves. For larger games of 12 and up, make it three.

One of the villagers is also given the role of the “seer”, also determined by the dealing of the cards at the beginning. More about the seer in a minute.

Gameplay alternates between “night” and “day” phases, with the moderator calling the shots. Kicking off with “night”, all players lower their heads, shut their eyes, and begin to drum on either the table or their legs, in order to drown out noise which could result in players gaining unfair information.

The moderator demands that all werewolves open their eyes. The wolves see who their teammates are, and must then nominate a victim to “kill” (silently, using hand gestures and signals). The nominated player is usually a villager, giving the wolves their first victim.

After the wolves have nominated their victim and closed their eyes, the moderator awakens the seer and asks him or her: “Seer, who would you like to ask about?”

The seer is then allowed to open their eyes and silently points to a player, careful not to reveal their identity to any other player. If the person chosen by the seer is a wolf, the moderator gives a thumbs up. If the player chosen is a villager, the moderator gives a thumbs down. The moderator then says, “Seer, close your eyes.”

When “night” comes to an end, the moderator asks every player to open their eyes before revealing which player was killed. This player is out, and must not reveal whether they were a villager or a wolf to the group.

“Day” then begins, with the majority of players unaware who is a villager and who is a wolf (only the werewolves know, while the seer might also know a wolf). For 10 to 15 minutes (it’s up to the moderator) players must begin to introduce themselves, debate, ask questions, hurl accusations, and ultimately vote on which player they’d like to kill. For the villagers, the hope is to kill off a wolf.

When a player has been selected, they leave the game without revealing their identity. The game then enters another “night” phase, and the pattern is repeated until all wolves are dead (a win for the villagers) or the wolves outnumber the villagers (a win for the wolves).

How a game of Werewolf looks during “night” (Credit: Creative Commons/Puik)

That’s the game in its most basic form. However, it’s common for more roles to be introduced, particularly in larger groups.

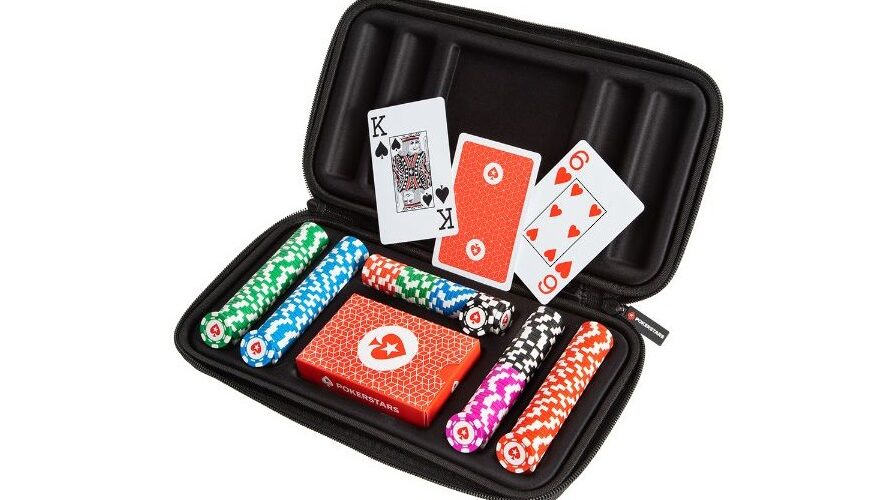

“It’s a credit to the game that you can play a very simple version with no kit: just two werewolves and a seer, without any other special roles,” Grafton says. “The guys at the PCA had a special kit though, which helps you balance the characters and gives you the optimal amount of werewolves for the size of the game.

“We were playing with 20 people at certain points, and you could easily misbalance a game that big and give the villagers a massive advantage.”

SPECIAL ROLES

The doctor

One villager is assigned the role of the “doctor”. After the wolves have nominated their victim in the first “night”, the moderator will tell the wolves to close their eyes. The moderator then awakens the doctor, asking him or her “Who would you like to heal?” This gives the doctor the chance to potentially save a player they think the wolves may have tried to kill.

The doctor (who also must not reveal their identity to any other player) silently selects a player, who will then survive even if killed by the wolves. As “day” begins the moderator will announce someone was saved, without revealing who.

The bodyguard

Like the doctor, the bodyguard is a villager who selects a player at “night” to save. The person they are guarding is told they are being guarded, but not by whom. If that player is then killed by the wolves during the next “night”, they survive and the bodyguard dies instead. The bodyguard can choose not to guard anyone at night, and may guard the same person multiple nights in a row.

A bit more info about the seer

The seer is vital to the game, but it’s a tricky role to play. You get the privilege of being able to confirm a player as a wolf or villager each “night”, but that could also get you into trouble. If you suddenly start accusing a player of being a wolf with everything you have, the wolves are going to be certain that you’re the seer. In that case, they’ll simply kill you off in the next “night”.

You have to play a balancing act, influencing your fellow villagers to vote a certain way without revealing your true identity to the wolves.

Got all that? Good. But just in case, here’s what you’d need for a 15-player game:

• One moderator

• Eight “villager” cards

• Three “werewolf” cards

• One “villager + doctor” card

• One “villager + seer” card

• One “villager + bodyguard” card

NOT FOR THE FAINT-HEARTED

Most party games are designed for relaxation. Only one player need stand up when playing charades, for example. And nobody really does anything in “Cards Against Humanity”.

Werewolf isn’t like other party games, and it’s for that same reason that it might not be for everyone.

“Some people just don’t want to play a game where there’s tension,” Grafton says. “Werewolf can seem quite personal at times. When you’re genuinely a villager and someone is accusing you of being a wolf, saying: ‘I’m looking at you and I can tell you’re lying!’, and you’re not lying, you can feel really pissed off at them.”

Sam Grafton, fast becoming a Werewolf reg

As we all know, poker players don’t mind a bit of tension. Nor do they mind unconstrained competitiveness. In fact, they embrace it, as Grafton explains.

“The intensity with which poker players take any game is crazy. I’ve played all sorts of games with poker players, and it’s simply not natural for everyone in society to take games incredibly seriously, and to play them to win at all costs. For us, that’s completely standard. So either you had that propensity before you got into poker and that’s what drew you to it and made you good at poker, or you don’t.”

It’s not just the competitiveness of Werewolf that make it the perfect game for poker players, though. So many elements seem to cross over, from the bluffing and the mathematics, to the GTO plays and exploitative strategies.

“A lot of the things we love about poker translate across to Werewolf,” Grafton says. “If you’re a good poker player the game should translate, especially if you’re a live player…Poker attunes you to people’s body language and mannerisms. Humans aren’t really built for lying and being stared at and being accused, so live poker players are actually ahead of the game in that respect.

“Another thing that’s a bit like poker is that you develop a metagame,” he continues. “You think: ‘Well, when they were a villager they were loud, and now they’re being quiet. Does that make them a wolf?’ It’s very easy to be loud and vocal when you’re a villager, and it’s much harder when you’re a wolf. If you suffer from that problem, you need to balance and dial it down.”

The game can get tense, and any signs of timidness will be pounced upon by experienced players. To counter this, the best players in a game of Werewolf tend to vote off new players straight away. “They’re less experienced and less likely to be a good villager,” Grafton says. “It’s kind of mean, but if you truly don’t know, we figured the best thing to do is vote off someone less likely to have a good strategy. If you’re inexperienced and suddenly 10 people start grilling you, a lot of people just give it up right away.”

On the flipside, good wolves will also tend to vote off strong people during the first “night”, so they’re prevented from meddling in their schemes. Jaffe and Joe McKeehen were the best at the PCA, according to Grafton (“When Jaffe isn’t a wolf he tends to get voted off straight away. The wolves kill him every night right out the gate. So it’s very obvious when he’s a wolf because he stays in the game longer than the opening round.”)

Jonathan Jaffe is one of the best Werewolf players, according to Sam Grafton

DAYTIME STRATEGY

Those first “daytime” talks can be a little awkward, particularly if you’ve never played before. However, keeping schtum and attempting to fly under the radar is counterintuitive. You’ve got to get yourself out there, especially as a villager, and fight your corner to survive. “You don’t really want quiet villagers, you want people who are going to speak a lot and try their best to work things out,” Grafton says.

Of course, it might help to quickly run over what you’re going to say in your head before blurting it out.

“I made a mistake and was really embarrassed the first time I was a werewolf with the PCA group,” Grafton adds. “I was put on the stand and started talking, saying: ‘Guys I’ve got no strong reads at the moment but I promise I’m not a villager,’ and blah blah blah. They then said: ‘Wait, what?’ And I said: ‘Oh I mean I promise I’m not a werewolf’. I’d made a Freudian slip, they picked up on it, and voted me off. I thought, well that was embarrassing.”

So, if you’ve organised a game with your friends, none of whom have played before, how should that first “daytime” round go? Grafton suggests having everyone make an opening statement. “That early round is an interesting one,” he says. “It’s amazing what people give up. It’s very hard to lie! You just want to get people speaking, don’t let anyone fly under the radar.”

As the game progresses and you become more comfortable in the environment, you might find your uncanny ability to lie incredibly well to your friends’ faces scares you a little. But don’t fret; keep the lying to the games of Werewolf and you’ll be just fine. Grafton remembers one particularly intense experience at the PCA where his ability to lie was proving very fruitful.

“We were playing with lots of special roles, and I was a wolf with two or three other wolves. All of the wolves got killed straight away, along with maybe two villagers. So it was 14-handed and I was the lone wolf remaining.

“People were asking for the special role players to come forward, and nobody came forward as the bodyguard. I knew as the last werewolf it would be extremely tough for me to win alone, so I pretended to be the bodyguard, and nobody else came forward for it. That meant we’d obviously killed the real bodyguard already.

“It was a very risky move because if someone else had come forward as the bodyguard, they could just kill me off right away as a wolf. Luckily everyone believed I was the bodyguard, and Joe McKeehen also came forward as a role. So, me, Joe and a couple of other people were proven villagers (even though I was really a wolf) and we were just killing people off one by one. I was completely safe.

“We killed everyone off until the only others remaining were Jerry Wong and Sam Panzica. It went to nighttime and we killed Sam, and as soon as we woke up Jerry knew I must be lying, because he was the last one remaining who we’d accused of being a wolf, and he knows he’s not a wolf. So basically we had two minutes of day time, and he’s saying to Joe — a confirmed villager — that I was a wolf.

Jerry Wong was ‘heads-up’ with Grafton in Werewolf

“Joe put us both on the stand and we had 30 seconds to talk, and I just had Joe staring me down and Jerry accusing me of being a werewolf. I was like: ‘Joe, bro, Jerry is the wolf, this is a desperation move.’ Joe had a minute and a half to think and the clock ticked all the way down, but ultimately he said I was the wolf and was right. I’d nearly made an MVP move of winning the game single-handed as the lone wolf, but Joe McKeehen was too good.”

At that moment, Grafton felt the same feelings he gets in a big High Roller.

“That experience felt like being in a poker tournament. I was being stared at constantly, and I had to maintain my story, and they were asking me lots of questions. It was very difficult! I think I can be a good liar, but when I’m saying: ‘Jerry is lying through his teeth!’ and I know he’s isn’t, it’s very hard to say it convincingly.”

So there you have it. You know the game. You know the rules. You know some basic strategy. Let us know when you’re organising your game of Werewolf and we’ll head on over.

Before we go, we had one last question for Grafton. Which poker player (who he is yet to play with) did he think would be great at Werewolf? And similarly, who was the worst player in the games?

“I imagine Stevie Chidwick would be pretty good because he’s inscrutable at the tables. But that’s when he’s not talking, so who knows?” Grafton says. “Jonathan Jaffe and Joe McKeehen are very good. Joe plays a good deceptive game.

Joe McKeehen was “too good”

“Toby Lewis is one of the worst. We put Toby on the stand and his ears went bright red. He went: ‘I’m…not…a werewolf…’ and we just went: ‘Yeah right, you’re dead!’ and killed him off straight away. It was one of the most pathetic attempts at playing werewolf I’ve ever seen in my life.”

Lesson learned. In a game like Werewolf, in which deception, manipulation and accusation are crucial, don’t let your ears go red. They’ll eat you alive.

Are you planning your own game of Werewolf? Let us know how it goes on Twitter at @PokerStarsBlog.

Back to TopView Other Blogs