If you asked poker players to create a list of reasons why they enjoy the game, chances are very few of them would rank “I like folding” anywhere near the top.

But most of us know being able to fold is an important part of doing well at poker. And if we can figure out how to like folding, well, that’s probably a good thing.

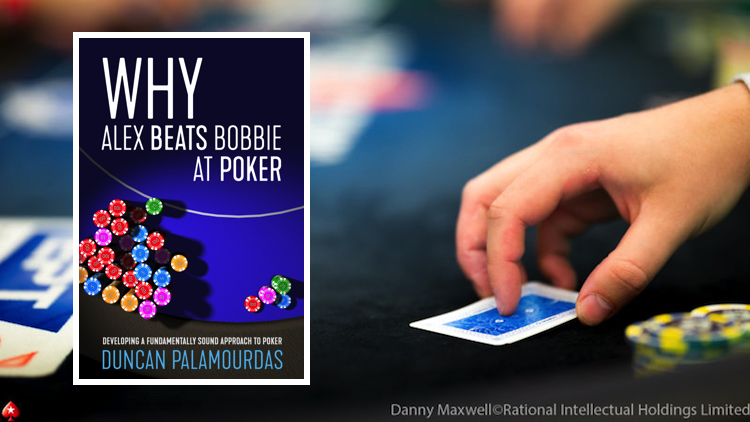

Poker author and UCLA math professor Duncan Palamourdas offers this recommendation in his brand new strategy book, Why Alex Beats Bobbie at Poker.

The book covers a wide range of practical poker advice and game theory. Palamourdas even delves into human psychology and some philosophy as he explains why some players (like “Alex”) consistently beat others (like “Bobbie”).

The book includes material Palamourdas has taught in his poker course at UCLA. As he does in class, in his book Palamourdas presents complicated topics in simple terms without resorting to technical jargon in order to help players sort through common scenarios and grasp important concepts.

Topics covered include:

- Understanding the instinctive but unprofitable tendencies of inexperienced players

- How to identify what a mistake actually is in poker – and how to exploit it

- Why poker does not revolve around bluffing

- The great impact of variance in poker and how to account for it

- How to develop a consistent approach that allows you to play like Alex and not Bobbie

The following excerpt comes from the chapter titled “We Are Only Human.” As the chapter title suggests, Palamourdas gets into some of those aspects of human psychology that can be so meaningful at the poker tables.

Here Palamourdas takes up that issue of folding and how much we humans who are “creatures of action” dislike doing it — and why we should learn to think differently about folding.

from “We Are Only Human”

Over the past several years, I have been incredibly fortunate to teach poker at UCLA. My students were made up of a very large and diverse group. Although the level of the classes ranged from total beginners (who did not even know the rules) to experienced players with years under their belt, it is pretty fair to say that the majority were fairly new to the game. This presented a unique opportunity to study some of the tendencies and raw instincts students brought to the game, that is before they learned how to control them and adjust. Needless to say, the majority of these impulses are deeply human and that is why they are so common among so many different types of people.

Moreover, although I have been observing people directly at the tables for a long time, watching students is a vastly different experience. When people are trying to learn they are not holding anything back, from openly sharing their thoughts and concerns, all the way to discussing their strategies and evaluating their own plays as well as those of their opponents, all while sharing their cards with the group. This is obviously not something you see at a casino very frequently, and certainly not to the extent that you would in a teaching session. Although it may seem like a small matter, it should be remembered that hole-cards are at the core of what poker is, separating it from perfect information games like chess or backgammon. I must admit that teaching has significantly changed the way I view people and their innate relationship with risk-taking. It is quite fascinating how many recurring patterns one observes if one looks long enough. We humans, after all, may not be as unpredictable as we would like to think. We are somewhat predictably unpredictable.

Without further ado, I would like to share some of these relatable instinctive tendencies, while looking for parallels in real life that addressed them, long before poker even existed.

1) I Didn’t Come All the Way Here to Fold!

People do not like to fold. Period. This should not be surprising. We are creatures of action, which means that once we decide to participate in something we usually do not like to passively wait on the sidelines. Reading this book, it in itself is very good evidence of that. Chances are, this means that actively improving your game is a high priority for you. This correlates to my hypothesis that you are likely not interested in just playing the game, but you also want to play it correctly and to maximum advantage!

In other words, it does not matter what the reason or the excuse may be; once we make it to the dance floor, it is time to dance! For example, we do not usually see recreational basketball players instinctively rejecting the ball from their more skillful teammates in order to increase their chances of winning. If they are there, they are likely there to play and playing means they should touch the ball, multiple times over and regardless of their skill. If they only wanted to watch other people battling it out without being involved, they could have stayed home and watched TV instead. Besides, the chances are that the TV game would be of a much higher quality anyway. I think this illustrates quite vividly our innate urge to participate once we are involved.

Poker is no different. People despise folding because it somehow feels that it defeats the purpose of what they are trying to accomplish. We are there to participate and to win as many pots as possible. Hence, folding feels almost like losing, or at the very least a waste of time. The feeling of inefficiency also enters. This is what most people call boredom. What’s the point of being involved in an activity that requires us to do nothing a good 80% of the time? This is a very powerful inner voice that can cause all sorts of anxiety and feelings of restlessness within us. It is so powerful in fact that it urges us to fight all that “inaction” by forcing ourselves to try all sorts of different things, not necessarily in the most effective manner: ill-timed bluffs, over aggression, or even pure gambling are some of the most typical reactions to boredom. It does not matter what the rationalization is for any of these actions, folding feels like a much worse alternative.

In reality, “being on the sidelines” is much more common than we might like to think. For starters, life is not an efficient process. An honest look within ourselves should probably be enough evidence of this. However, for those interested in less subjective evidence, dissecting the inner processes of any government in the world (or any other large organization for that matter) should definitely do the trick. We can even be more specific than that: take firefighters, arguably one of the most useful jobs in society. Their expertise is used only as needed by the rest of us. This means that they will have to face some inevitable “down time,” when things are not as hectic. Or take kickers in American football, a very specialized, but also invaluable position in a game. Their only role is to kick the ball at very specific times during the game and yet some of them earn more than $1.5 million a year.

The point is, inefficiency and down time are inevitable no matter what we do. However, this does not necessarily mean inaction. Both firefighters and kickers who are worth their salt spend a lot of their down time training and perfecting their craft. Successful poker players do something similar. They use their “down time” to study their opponents and gain valuable information on their tendencies and tactics. The best players also use the opportunity to test their deduction skills. They do that by guessing what their opponents have, even when they are not in the hand! Alex, for example, could observe Bob and Charlie betting, calling and raising one another. Immediately after each action, she updates her theory of what these two gentlemen could be holding. Then she can test her theory during showdown, if and when it gets there. Did Bob and Charlie show the type of hands Alex was expecting? If yes great, but if not, she can adjust her assumptions accordingly! Either way, she is gaining valuable information. Undoubtedly, studying other humans or playing Sherlock Holmes at the table is not everyone’s cup of tea and neither should it be. That being said, “dead” time is a big part of the game. Thus, like the best servicemen and athletes, a successful poker player needs to embrace the times of no action and use those as an opportunity to advance their skill. Otherwise, the game may quickly turn stale.

“Why Alex Beats Bobbie at Poker” by Duncan Palamourdas

Duncan Palamourdas’ Why Alex Beats Bobbie at Poker is available in paperback or as an e-book from D&B Poker.

D&B Publishing (using the imprint D&B Poker) was created by Dan Addelman and Byron Jacobs 15 years ago. Since then it has become one of the leading publishers of poker books with titles by Phil Hellmuth, Jonathan Little, Mike Sexton, Chris Moorman, Dr. Patricia Cardner, Lance Bradley, Martin Harris and more, all of which are available at D&B Poker.

Back to TopView Other Blogs