Yesterday the poker world was saddened by news of the passing of one of best ever to write about the game, Al Alvarez. The British writer, poet, and critic died after succumbing to viral pneumonia. He was 90.

Alvarez’s stature as a man of letters was formidable, well established by an eclectic canon of books and essays that reflected his wide-ranging interests. In literary circles he is best known for having introduced Sylvia Plath and other modern poets to a wider audience. In the early 1970s his in-depth study of suicide The Savage God was a bestseller, and remains influential today. Works on divorce, rock climbing, swimming, and other topics — all providing occasions for literary deep-dives into existential questions about the meaning of life — further solidified his status as a wise and discerning commentator on the human condition.

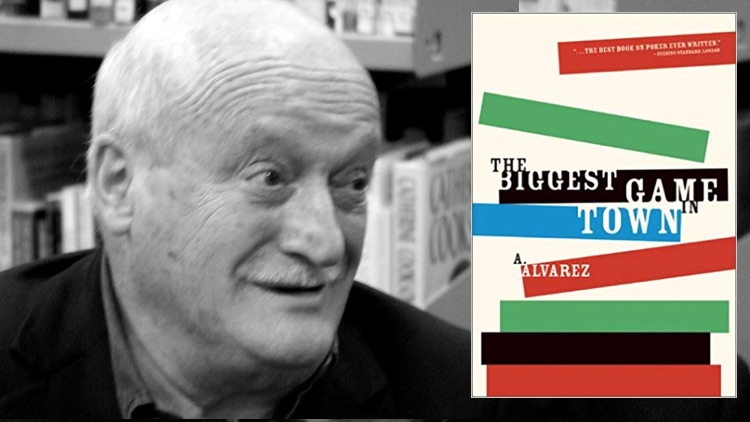

Alvarez was also an avid poker player, and in 1981 received an assignment to cover the World Series of Poker in Las Vegas for The New Yorker. The result was a lengthy feature spread over two issues titled “A Reporter at Large (Poker World Series)” later published in book form in 1983 as The Biggest Game in Town.

Al Alvarez, “The Biggest Game in Town” (1983)

It is, in short, the gold standard in poker reporting. I’m hardly alone in that opinion. Not only does Alvarez provide a valuable historical account of that year’s tournaments and participants culminating in Stu Ungar’s Main Event title defense, the book brilliantly shows what makes poker such a fascinating game to so many while also particularly delivering an absorbing, enlightening portrait of Las Vegas and, by extension, the United States.

Starting with the symbolic seven-foot-high horseshoe with a million dollars under glass at the Binion’s entrance (“the perennial dream of the Las Vegas punter visible to all, although not quite touchable”), Alvarez lyrically sketches the high rollers’ rituals as he explains “the differing order of reality” to which many of them appear to adhere. His observations are complemented by many interviews, including with Johnny Moss, Doyle Brunson, Chip Reese, Eric Drache, Mickey Appleman, David Sklansky, and Jack Binion.

While presenting those and other characters Alvarez artfully addresses larger themes as well as including societal attitudes toward poker and gambling, the romance of poker and how it clashes with the reality. He explores how full-time players train themselves to think of poker as “work” (instead of “play”), how in poker money can somehow simultaneously mean everything and nothing, and the oddly-independent subculture of poker players and how the game provides some a kind of escape from the “straight world” or “system”.

It’s a relatively slim volume, but nonetheless contains a multitude of poker-related maxims that have become some of the most-quoted lines the game has produced. Some of them Alvarez compiles from others, for example, “Limit poker is a science, but no-limit is an art. In limit you are shooting at a target. In no-limit, the target comes alive and shoots back at you” (Crandall Addington); “Money is just the yardstick by which you measure your success” (Chip Reese); “The next best thing to gambling and winning is gambling and losing” (Nick “the Greek” Dandolos); “The game exemplifies the worst aspects of capitalism that have made our country so great” (Walter Matthau); “If there’s no risk in losing, there’s no high in winning” (Jack Straus).

Among those aphorisms Alvarez shares many of his own poker proverbs as well. For example: “Chips are not just a way of keeping score; they combine with the cards to form the very language of the game.” Or: “When the cards are particularly kind, even a sucker can beat a really good player. But not for long. That is why the poker tables at Las Vegas are called ‘the graveyards of hometown champs.'” Or: “In poker, as in everything else, imagination starts where logic falters, and transforms reality for its own ends.”

The story ends with an account of Ungar’s Main Event win, and in his description of the action Alvarez betrays the poet’s sensibilities to pleasurable effect: “The chips were like rapiers in a fencing match — instruments to attack, parry, counterthrust until one or the other of the duelists deliver the coup de grâce…The rustling, whirring calm that passes for silence in Binion’s Horseshoe thickened, like the air before a thunderstorm…” At last comes the final hand, after which security guards come “carrying bundles of money, which they heaped prodigally, like firewood, on the table.”

The book was a hit, going through many editions and still frequently read and recommended by poker players. Before Rounders, the “Moneymaker Effect,” and the “boom” sparked by online and televised poker, The Biggest Game in Town introduced both Texas hold’em and the WSOP to a mainstream audience in the most effective way possible — via an engaging, masterfully told report.

Al Alvarez, “Poker: Bets, Bluffs and Bad Beats” (2001)

Among other literary efforts, Alvarez continued to write about poker. His 2001 title Poker: Bets, Bluffs and Bad Beats presents eight more excellent essays about the game (an introduction plus seven chapters) along with a glorious collection of images and photographs from game’s long history.

In “The American Game” Alvarez directly addresses how poker uniquely reflects the character of the country in which the game originated, employing familiar wit while mixing tributes with teases. “Poker is more than the national game: it is part of the American way of life,” he writes, “the treasured part that allows Americans to indulge in their passion for toughness without the tedious business of staying trim and fit.”

Subsequent essays on the game’s history and most famous hands, poker’s intellectual and mental challenges, the significance of money to poker, and the centrality of bluffing to the game provide further insight.

The book culminates with an adaptation of another New Yorker piece, this one recounting Alvarez’s return to the WSOP in 1994 to play cash games and in three events. A head-spinning good run of cards in a $2,500 event inspires Alvarez to perform a bit of self-deprecating self-analysis (“Psychoanalysts call this state of mind ‘mania’; the poker pros describe it more vividly: ‘He wanted to give his money away,’ they say, ‘but the cards wouldn’t let him.'”) After detailing his bustout from the Main Event, Alvarez evokes Adlai Stevenson who lost presidential races twice in the 1950s. (“He said he was too old to cry, but it hurt too much to laugh. I know how he felt.”) Introducing the novelty of that year’s winner being awarded his weight in silver prompts another ready analogy (“In best prizefight style, there was a weigh-in before the start”).

Again, with Poker: Bets, Bluffs and Bad Beats Alvarez provides those who write and report on poker — and those who enjoy reading about it — yet another model demonstrating the very best the form can offer.

Writing about his own adventures at the tables was something Alvarez had in common with his friends and poker buddies, David Spanier and Anthony Holden, both of whom participated with Alvarez in their famed Tuesday Night Game. Both also wrote their own poker books, with Spanier’s 1977 collection of essays Total Poker and Holden’s 1990 title Big Deal establishing with Biggest Game an essential trilogy of nonfiction poker titles for anyone with an interest in the game. Along with them Alvarez inspired later writers of poker narratives like Jesse May, Victoria Coren, James McManus, and others to explore their own fascination with poker by writing about it.

RIP Al Alvarez: a great man, who loved poker enough to write one of its seminal books yet remembered also to see the world, climb mountains and have a million other adventures. He didn’t just play online in a onesie. I wanted to be like him, and I’m so sorry he’s left the game.

— Victoria Coren Mitchell (@VictoriaCoren) September 24, 2019

I just learned that Al Alvarez has passed away. He wrote arguably the best narrative about poker, ever, “Biggest Game In Town”. You read it, you can smell the smoke at Binion’s. And his poker writing was really a side project to an amazing literary career. RIP one of the best.

— Lee Jones (@leehjones) September 24, 2019

When Al Alvarez was asked for his luxury item on ‘Desert Island Discs’ – which he was invited on as an outstanding poet and critic – he asked for internet connection so he could play online poker. A true ambassador.

— Sam Grafton (@SquidPoker) September 24, 2019

His initials connoted hold’em’s best starting hand. Al Alvarez’s writings about poker will likewise continue to top the rankings of works written about the game.

Read more about Al Alvarez’s amazing life in The Guardian and The New York Times. I also write more about Alvarez and The Biggest Game in Town in Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America’s Favorite Card Game.

Back to TopView Other Blogs